Here’s a strange little detail about the 20-car pile-up that is the Ontario Place redevelopment scheme: Shortly before Christmas, the province posted a heritage impact assessment (HIA) on its EngageOntarioplace.ca website. The document contained what, for me, was an ah-ha detail about a plan that has continued to evolve behind the scenes ever since the earliest version surfaced last summer at Waterfront Toronto’s design review panel.

The project has grown to include a $450 million, 2,100-space underground parking garage. Updates to the plans also began to reference a “science pavilion,” to be located on top of said garage, which would replace the west parking lot.

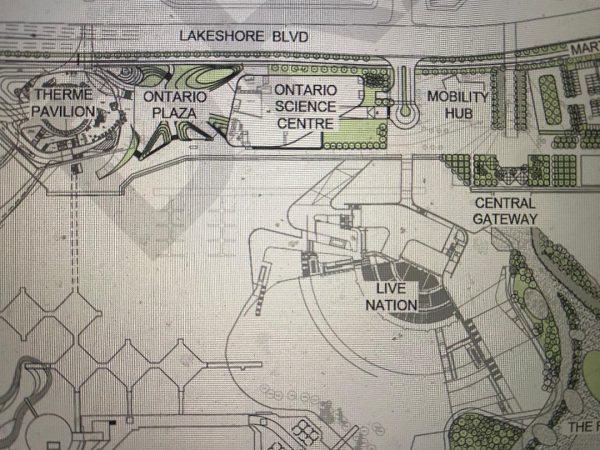

A schematic in the HIA confirmed what many observers had begun to suspect, which is that the “pavilion” will become the new home for the Ontario Science Centre. That reference, which I noticed in late December, has since vanished from the document, likely since The Globe and Mail‘s architecture critic Alex Bozikovic alluded to it in his harsh assessment of the design of the Therme spa, which he predicted would become Toronto’s “worst building.”

This (perhaps inadvertent) surfacing of what might be happening at the other end of the Ontario Line, which will extend from the CNE to Don Mills and Eglinton, is not only a crucial piece of the puzzle, but one that offers the province a way out of this extravagant mess.

The draft HIA, prepared by ERA Architects and commissioned by Infrastructure Ontario, is a document required under provincial planning law and subject to public consultation (feedback will be accepted through January 20th). Although the 140-page report doesn’t use these words, it poses the eternal question: can you put lipstick on this pig? And will it help?

The HIA proposes a series of design tweaks that aim to mitigate the visual and experiential impact of a nine-storey glass and aluminum blob that will dominate the west island in every conceivable way.

These moves, which appear to have been pre-negotiated with Diamond Schmitt, the project architect, include adding some porousness to the bridge to the spa in order to ensure slightly better views of the pods and pavilions; commemoration plaques and documentation; and additional tree retention “where possible” (the Therme plan removes some 800 trees).

The HIA also suggests that the massing of the new “megastructures” — i.e., the spa and the expanded Live Nation stage — be ‘sculpted,’ with additional step-backs and setbacks meant to protect “approach views” of Ontario Place’s signature structures from the east and west.

The reality is that the sprawling spa buildings will still be, to switch cliches, the elephant in the room that was Ontario Place, leaving little space for much else at its edges.

The heritage and environmental impact is, in fact, enormous, and this key point has been getting an increasing amount of public, political and media attention. Yesterday, in fact, former mayor David Crombie released a scathing public letter to Mayor John Tory and the members of city council, denouncing the Therme plan as “abysmally tone-deaf” and imploring them to protect Ontario Place and the west island in particular as invaluable green space.

There’s a certain ambiguity about the discussion of heritage impact. Certainly, Eb Zeidler’s architecture and Michael Hough’s landscaping provide the formal foundation for Ontario Place’s heritage. But because of its closure in 2012, the 2017 opening of Trillium Park and finally the pandemic, Ontario Place’s appeal, as Crombie duly notes, is very much a living thing, emanating from the way many people, including those living in the vertical neighbourhoods nearby, have re-discovered it as a park during and since the lockdowns.

In an interesting and important way, ordinary city-dwellers, without the help of planners or capital, have created an adaptive re-use for the landscape of Ontario Place, which, as all heritage planners will attest, is the high-water mark of heritage preservation.

ERA’s report doesn’t really address this user-driven evolution, but it does bruit another important possibility — a future life for Zeidler’s unique pods, which always struggled to find a purpose. Such as step is “critical to the conservation of cultural heritage value at Ontario Place,” notes the HIA. “The Megastructures have great potential as a catalyst for broader revitalization and site activation; their adaptive re-use should be prioritized accordingly.”

The notion of re-locating the Science Centre to Ontario Place (which was proposed informally to the Wynne government) and incorporating the pods as exhibit spaces, represents an ideal adaptive re-use, and unlocks a range of wins for both the city and the provincial government, while ridding Toronto of what will be an epic mistake by the lake.

To get there, however, we need to have a wide-open debate about both ends of the Ontario Line, which the province seems to not want to do.

First, if Doug Ford’s Tories are prepared to sink over half a billion dollars into Ontario Place in order to make it attractive to spa goers, we need to ask how else all that public money could be spent in order to revitalize this space. What is the opportunity cost?

The Science Centre, in its present location, has been a fading enterprise for years, and the buildings are now in need of major repair. More importantly, its two vast parking lots sit between a pair of future subway stations (Flemingdon Park and Science Centre, with the latter serving a major transit interchange (with the Eglinton Crosstown).

The city knows and is planning for the intensification of the Don Mills/Eglinton node, which is already designated as a major transit station area, meaning it will be zoned to attract a lot of density. From a planning perspective, it is insane to have two huge publicly-owned parking lots book-ended by subway stops; in short, the Science Centre lands that front onto Don Mills Road must be seriously intensified with offices, apartments and community amenities.

Relocating the Science Centre to Ontario Place enables the evolution of that intersection, and also allows for the adaptive re-use its structures as community amenities.

Down at Ontario Place, meanwhile, the Science Centre becomes the visitor attraction that the Tory government craves, allows for a second life for Zeidler’s pods, and protects the already adaptively re-used west island as public green space. No trees or birds will be harmed.

It’s also worth saying that from a programmatic perspective, the OSC has huge potential. Compared to when it opened in the 1970s, Ontario today is far more focused on science, technology, and innovation, as well as the fruits of all that inquiry, in fields like biomedical research, cleantech, and computing. A renewed version of the Science Centre can go well beyond static electricity up-dos and IMAX’s planetarium films for school groups.

There’s clearly someone at Queen’s Park thinking these thoughts. It’s well past time that we allow those conversations to occur in public. The Ford government has a way out of this disastrous venture, as well as a bridge to something much better. All the premier has to do now is open his eyes, stop listening to Therme’s lobbyists, and do the right thing.

top photo form Toronto Archives (fonds 124, file 9, id 41)

The post LORINC: Can the Ontario Science Centre save Ontario Place? appeared first on Spacing Toronto.