Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A month from now, the City, Toronto Western Hospital, and an Enwave spin-off called Noventa Energy will unveil one of those alchemy-like projects that transforms a societal cast-off into modern gold.

In this case, the cast-off is all that raw, warm, fast-flowing sewage running through a big old interceptor pipe under Dundas Street. The gold, in turn, is the heat energy that can — with some serious engineering interventions — be sifted out of the pipe and used to replace about 90% of the natural gas that currently powers the hospital’s physical plant. “It’s not a small amount,” says Fernando Carou, the City’s manager of public energy initiatives.

This energy from waste-water project, the first of its kind in Toronto and a technical variation on the ten-year-old facility in Vancouver’s False Creek, poses the intriguing possibility of using locally-produced human waste to offset locally-consumed fossil fuel in what could be described as a pungent application of the promise of circular economy principles for reducing carbon.

While the early planning for this undertaking pre-dates the pandemic, it will also serve as an illustration of what robust urban resilience demands as we head into an era in which every person will have experienced first-hand the extraordinary disruption of a global crisis.

Yet just as we’ve learned that true pandemic preparedness in the future needs to be about a whole lot more than just infectious disease control, this kind of venture illustrates that pushing the boundaries of local climate resilience raises gnarly technical, financial and policy riddles that must be sorted out in a rapidly closing window.

With apologies to Telus, the future will be complicated.

Noventa Energy Partners was founded in 2018 by former city councillor and Enwave CEO Dennis Fotinos, who had discovered Huber, a Bavarian water treatment engineering company that had developed a technology to draw heat energy from sewage. Noventa has secured an exclusive license to distribute the system, and last month signed contracts for three other pilot projects in Seattle, Washington, and surrounding King County.

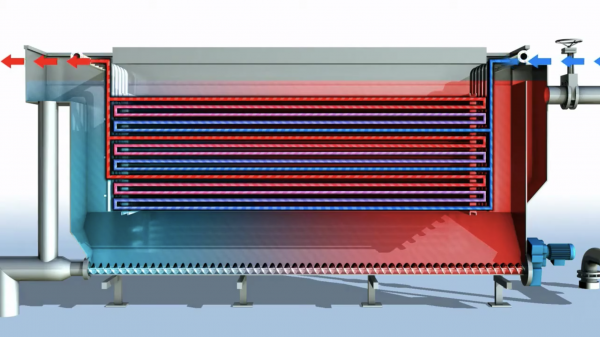

The concept of a heat exchanger isn’t new: it’s basically a set of highly conductive pipes through which a hot liquid flows. The conductive material draws the heat out of the liquid and transfers the energy into some other form. The problem in attempting this trick with sewage is that the sludge, though warm, is thick and corrosive, and befouls conventional heat exchangers.

Huber’s solution is to build a deep steel-lined holding tank near a sewer main, with a narrow pipe connecting the two so some of the flow is siphoned off. In the tank, the floatables settle out and are then returned to the sewer main. The remaining brown water, in turn, is run through a heat exchanger and then also pumped back into the city trunk line, albeit at a lower temperature. The heat is upgraded in an electric heat pump and can now be circulated in an nearby building, thus offsetting any natural gas used in the heating systems. The sewer liquid merely passes through the heat exchanger and back into the waste water system.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

With the Toronto Western project, all this subterranean infrastructure will be installed next to the Scadding Court Community Centre and under Dundas. Construction begins later in the spring and is expected be complete next year. Over the 30 year life of the agreement, Noventa pays the City an annual $180,000 energy transfer fee, according to Fotinos. Western, in turn, will pay Noventa to supply the heat. The Atmospheric Fund is also a financial partner. The company’s anticipated rate-of-return is 9 to 10%.

Noventa is working on three other similar ventures, supplying wastewater heat energy to the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, near Sunnybrook, Holland-Bloorview Kids Rehab and Etobicoke General Hospital. (A proposed 2019 deal with Sunnybrook was cancelled.)

While these projects do break ground, the City is by no means oblivious to the energy and carbon trapped in waste. The large sewage treatment plants, like Ashbridges Bay, sell huge quantities of de-watered biosolids for agricultural uses or mine reclamation, although plenty of this stuff ends up in landfill. And over the past five years, the City’s waste management division has been working to use biogas from landfill sites as renewable natural gas (RNG). A 15-year pilot with Enbridge began in 2018, with the goal of supplying 65 million cubic metres of RNG annually — equivalent, the City says, to removing 35,000 cars from the roads each year.

With the sewer water, Carou, the city official overseeing the Western project, says his team is currently “mapping the resource,” but estimates that the heat trapped all that daily sludge could be roughly equivalent to the capacity of the 550-MW natural gas-powered Portlands Energy Centre, which generates enough electricity to supply about 450,000 homes. Other academic analyses suggest that the energy trapped in sewage is up to ten times the amount necessary to treat wastewater in a large treatment plant.

There are, of course, wrinkles, even beyond the engineering complexities.

One involves a weird inversion of the riparian rights problem. The heat content of sewage downstream from one of these facilities will be lower than upstream, meaning that the next one to be constructed would have to be far enough along that sufficient new sewage flows in to the main to replace the heat siphoned off at the previous site. Likewise, as Fotinos notes, a customer like Western doesn’t want a new facility to be situated too close on the upstream side so as not to eat into its anticipated supply. Like Starbucks locations, they have to be properly spaced out.

Then there’s the money question.

Does sewage heat have economic value? Yes. Who owns it? Well, if you used the toilet in the city, you might consider yourself a shareholder.

What is the appropriate price? Not clear, although it has to be slightly less than natural gas to make sense. As the private sector operator supplying the equipment, signing on to some of the risk and operating the service, Noventa wants to earn a profit. But the City, as owner of the resource, must also take steps to ensure it’s not leaving money on the table. In this case, the end user, a public hospital, has no profit motive, but the negotiation over rates could become more difficult if Noventa is able to add office buildings or condos to its roster of clients.

If the technology is reliable and the approach can be scaled up so there are sites across the city, the benefits will go some distance toward reducing the City’s natural gas consumption. It’s also possible that the windfall could be re-invested in other clean energy, transit or green building projects – another example of how the city can create virtuous circles by up-cycling the energy we all flush down the drain each day.

Yet to achieve all this, and thus move Toronto a bit closer to something akin to energy self-sufficiency, the City, emerging clean energy utilities like Noventa and other end-users will need to shoulder through the countless technical complexities and policy potholes that will pop up along the way. In other words, the energy, persistence and capital required to transform these kinds of long-shot pilots into fully-realized systems must also be part of this story.

As the past year has shown us so clearly, resilience is needed to build resilience.

The post LORINC: The Power of Poop appeared first on Spacing Toronto.